Whenever I ask someone about their literacy journey--why reading matters; why books are important--I rarely get a response that’s just about books or words or test scores. What I get are stories of families reading together, of an event focused on reading, of a favorite teacher’s passion. That suggests literacy is about much more than learning words on a page. It comes from a community that values literacy and families that share their love of reading with their children. It’s about educators connecting with homes and partnering in the literacy experience. It’s communities collaborating to make books and reading central to children’s development.

A case in point: Recently, at an Omaha elementary school, Yanki Smith read a book to the class that she wrote with co-author Barb Stratman about strategies for helping children cope with moving. She wrote the book not only to help her own children, who are featured in the text, but also to help other families in the community going through the same thing. In fact, Stratman says that Canopy South, the organization she works for, gives the books to other families who are in the moving process.

The connections here between individual families, their local community, and the educational system already become evident, but there’s more. Greta Carlson, who took over from Wendy Keele as program manager of Nebraska Growing Readers (NGR), the initiative that published Smith’s book, was in the classroom that day. After the reading, children went back to their desks to look at the book on their own. Many used their school Ipads to scan the barcode that took them to the Nebraska Growing Readers digital library.

Carlson noticed that a young boy had found the section of the library platform that showed texts in different languages. When she asked him if he wanted to listen to a book in a different language, the boy asked, “Do you have my language?” When she was able to pull up a book in his native Karen, Carlson said, “his whole face lit up when he heard his language.” She notes that his English was excellent and that he’d probably only heard English texts in school, but that his literacy journey in one click of a button had bridged from school to home and his own family's experiences.

Josh Cramer, who is Senior Vice President of Nebraska Families and Children Foundation, the organization that has partnered with the Nebraska Department of Education and Unite for Literacy, to create NGR, says of such moments, “it’s really cool to see local Nebraskans seeing themselves in these books and then reading those books and using that to build their own literacy skills.” That’s one of the basic tenets of NGR, creating local content reflective of the traditions and values of the community. Such local content, combined with ensuring children have access to books in the home and that families adopt shared reading habits, has formed the foundations of NGR.

To understand why, you have to go back a bit. Mike McGuffee, CEO of Unite for Literacy, began his career as an elementary science teacher. In 1988, he received a Christa McAuliffe Fellowship to research math and science and, by happenstance, attended a literacy conference in Arizona, where he connected with the University of Arizona and an Eisenhower Grant they were using for literacy research. The fieldwork he did there took him to communities where he saw “some homes without running water or no electricity and definitely no books.” He saw an opportunity not only to provide books but also to create content that connected to the local environments he visited. Because he had written some children’s books and had basic knowledge of layout and design, he was able to team with local representatives to take pictures on a Sony Mavica camera with a floppy disk that held roughly 15 pictures and write the stories of the photos they had taken. Throw in inexpensive comb binding and you had the books they called Webbes (Web Books for Everyone) that could be distributed to communities so they could begin building home libraries. Those books became the models for what, in 2012, was formalized into Unite for Literacy.

From its beginning, Unite has been about families in many ways. One of the core principles of the organization has been that more books in the home result in higher academic achievement. To promote the best outcomes, however, Unite has paired its push to build home libraries with efforts to encourage families to read together. It is at this intersection of more books in the home and the adoption of shared reading habits that Unite sees an optimal zone of literacy gains.

Even the organization itself has become a family affair. Mike’s son Nick followed in his father’s footsteps and became an educator. After teaching in Colombia and Korea, he decided to join the Unite team and soon found himself in Mexico helping translate many of the books into Spanish. Nick says of the ideas central to Unite, “it’s a family community-based family literacy model--we’re focused on a holistic solution.”

Unite had taken its family model to individual school districts, non-profits, and even to local governments in the U.S. Nick said, they’d worked with roughly 8-10 states previously, but their books had been read in every county in the country and in many countries outside the U.S. But in the post-covid years, a bigger project started to take shape.

One of the organizations that supported the early work Mike was doing was the National Center for Family Learning (NCFL), and it was here that he met Josh Cramer, who worked for NCFL at the time. Cramer describes himself as a “lifelong literacy advocate,” so when he connected with Mike, the die for bigger pursuits was cast. Cramer soon returned to his home state of Nebraska where he took on his position at Nebraska Children and where he said to Mike, “I would like to see Nebraska lead the nation in family literacy programs.” The two then began discussing a way to make Nebraska Unite’s first statewide literacy effort.

One of the concepts Unite had first become known for was a term Mike coined, “the book desert,” which were areas where access to books was limited and where families often had few or no books in the home. Unite was able to identify these areas and represent them in a book desert map of the U. S. What that told Mike was that the problem was structural. What he saw was that communities where schools showed high academic achievement were also communities with high access to books and high levels of shared reading among families. Conversely, low-achievement schools were likely to have less access to books and lower levels of shared reading. The question then was how to create necessary literacy infrastructure in the latter communities.

The problem of creating infrastructure thus became much more crucial when addressing the statewide needs of Nebraska. Cramer, however, saw the potential of utilizing Sixpence, a Nebraska Children initiative, and their connections around the state with early childhood educators, ESUs, school districts, and community advocates. The partnership between Nebraska Children, Unite, and the Nebraska Department of Education was thus formed and became Nebraska Growing Readers in 2023.

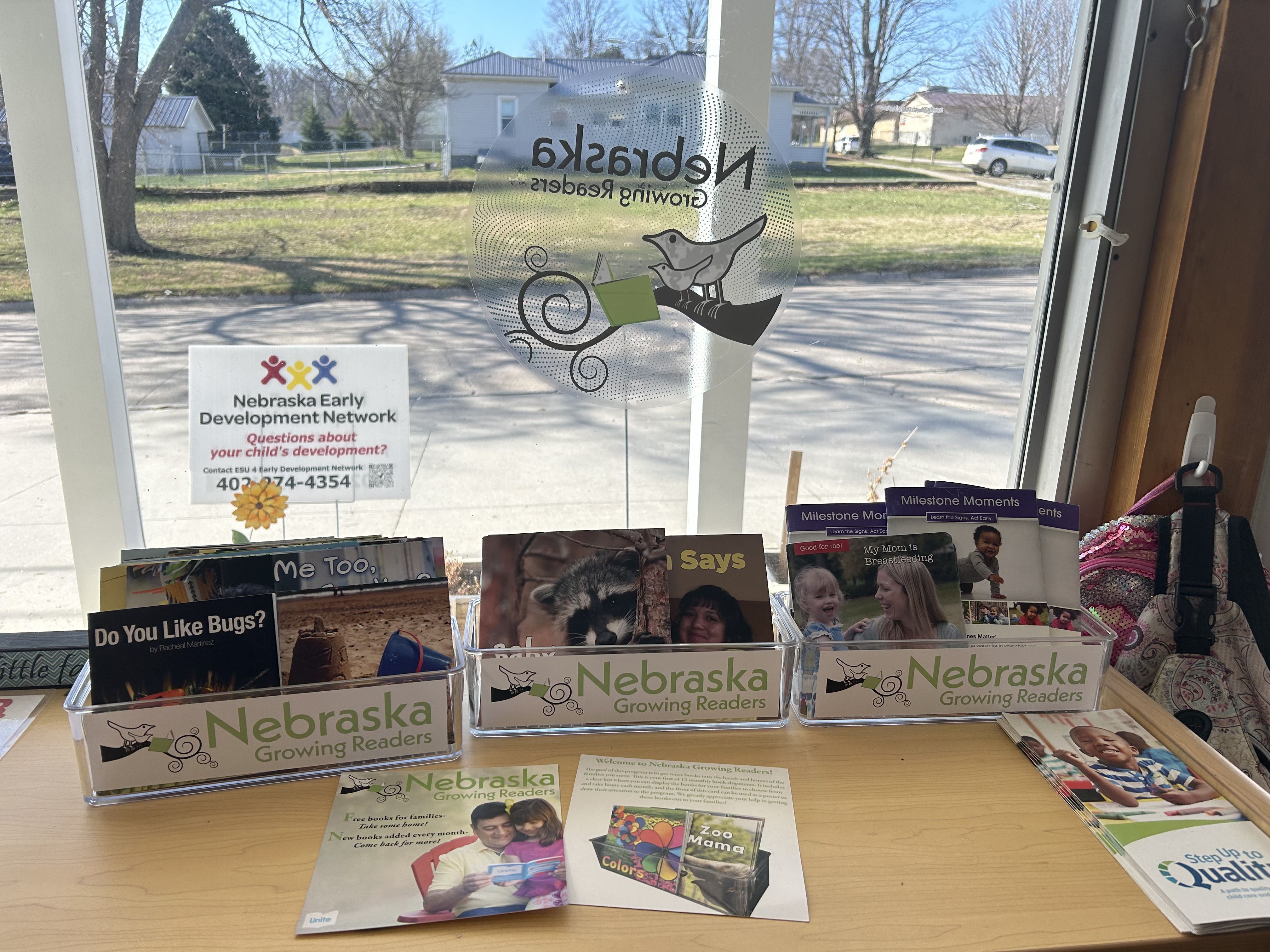

In its first year, NGR has rapidly developed outreach in communities all over the state. Carlson says that they tried “to engage every county in the state, even if they didn’t have licensed child care providers.” The year began with an offer to licensed providers to receive free books for their families when they registered with NGR. The initiative met the target goal of 1,000 providers in less than six months, and when NGR then offered incoming kindergartners free books to be mailed to their homes, the 3,000-student goal was met in just over a month. NGR began offering writer’s workshops to encourage local authors to create content related to Nebraska, which soon resulted in 37 books written by 33 local authors. The initiative also began to partner with communities to offer Book Gardens, areas where public book stands provided an opportunity for kids and families to grab free, age-appropriate books to take home.

NGR has quickly begun to build an infrastructure to ensure books can get to the families that need them and has worked to promote shared-reading habits by holding events such as book signings, book breakfasts, and promotional events such as the Touch-a-Truck event. The result has been a significant and swift success. Nick admits that in some previous Unite efforts it has sometimes been a challenge to register people for free books, but, he says of Nebraska, “we were able to really make a difference across the state and have really strong relationships through Nebraska Children.”

To demonstrate Nebraska’s early journey in this literacy initiative, Unite has created a story map, which Nick says, “makes the problem visible, makes the indicators visible, makes the solutions visible, and makes the outcomes visible.” The story map includes the book desert map as well as other interactive maps where viewers can see crucial data concerning Nebraska tests scores, optimal reading zones, and more. But the map also brings the state’s literacy journey to life through: photos of book events, such as a book basket decorating event at Educare Indian Hill; pictures of the families impacted by book stands in libraries, health centers, and businesses around the state; stories such as that of Jeter who has a rare genetic disorder that makes communication hard but who spoke his name aloud for the first time when he saw himself in the NGR book Rare is Beautiful. Carlson said of the map, “when I scroll through it, it’s like watching a story unfold; there’s a nice little narration talking me through the maps.”

But story is one thing. As Carlson put it, “the distribution part is relatively easy once the system is set up. It’s understanding impact and efficacy that takes more work.” That’s why the recent results from a Munroe-Meyer Institute evaluation of the program have been so encouraging. The report that studied the impact of NGR efforts on book availability and shared reading habits found that “Early childcare providers reported notable increases in reading frequency with children and the availability and ease of access to books in classrooms.” It also revealed that not only were books more available in the homes studied, but that families reported increased reading frequency. Furthermore, there was “improvement in selected language and literacy skills.”

These early results indicate that NGR is working toward the goals the initiative established, but Mike emphasizes, using the garden metaphor central to NGR’s work, “we’ve really just prepared the soil; maybe planted a few seeds.” He notes that there’s more work to be done but does underscore, “Nebraska is primed to really lead this work as a state.” Cramer feels that Nebraska children is prepared to do that. “We know that we’ve made an impact on literacy skills and communication skills in young children. And that’s a big deal!” he says. What he’d like to see for the future is that enough funding is identified for every kindergartener to receive NGR books in the home and “benefit from the interactive/intergenerational literary strategies.”

In the year ahead, NGR will distribute books to families connected to Sixpence early childhood providers and home visitors. They will also be offering opportunities for Educational Service Units (ESUs) to implement a number of literacy programs that, as Cramer says, are about “intergenerational literacy skills, about books, about children and families reading together.”

But Carlson points to other impacts the initiative could have. She says, “it’s not just reading together. You get so much from that process: that’s secure attachment bonding, your child sitting in your lap, reading books together, even for 5 minutes. It’s so important.” She further offers an instance where a 2nd grader who struggled with reading used the books to read to his younger brother.

What NGR represents then is larger than reading or books. While book availability and the adoption of shared reading habits are the crucial infrastructure on which to build a literacy environment, literacy shapes relationships, those between parent and child, between families and educators, that echo into the community.