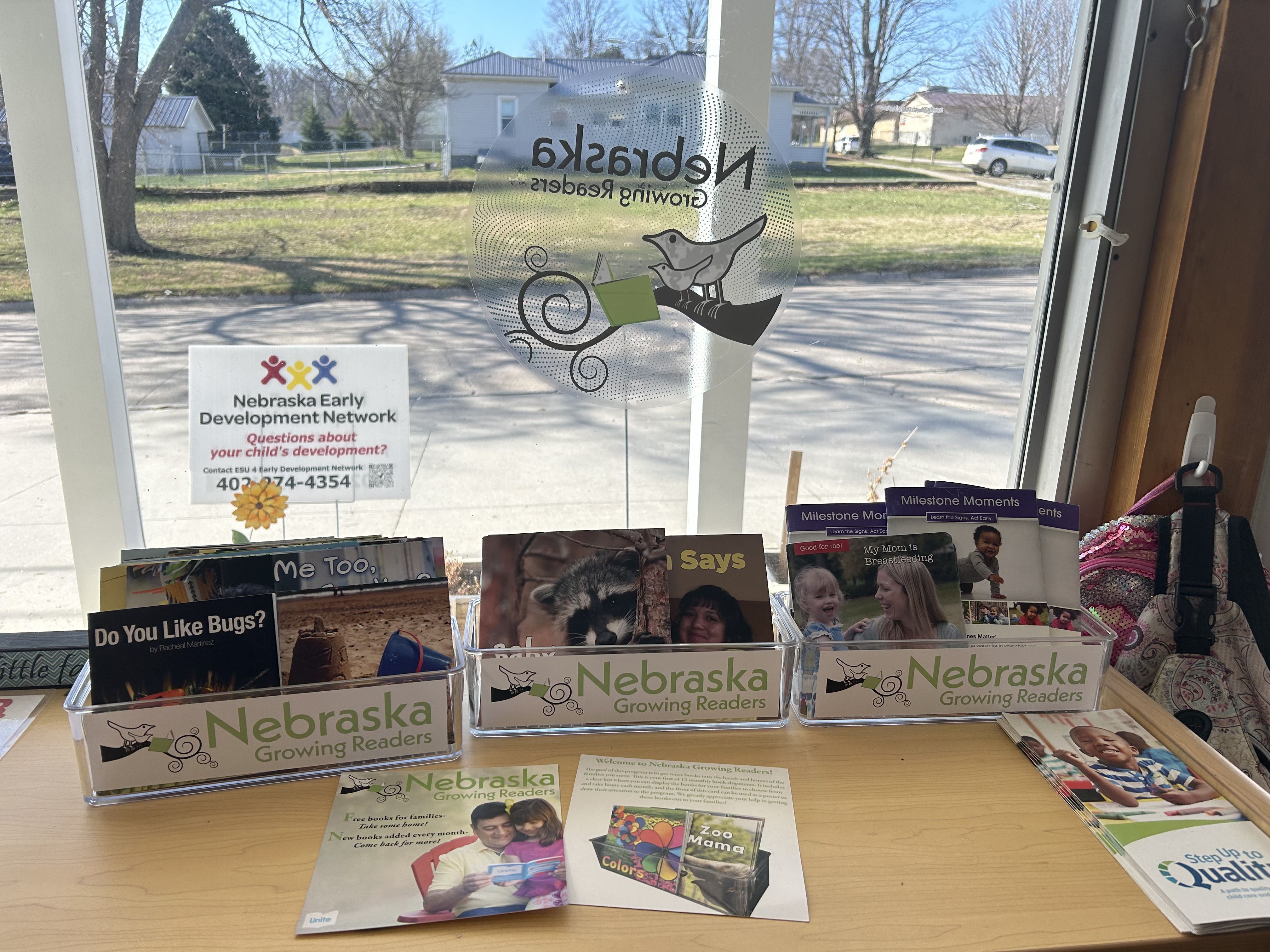

“She would look at the pictures and tear the books up!” Rosa Alvarado describes an unusual beginning to a success story for Sixpence and Nebraska Growing Readers, both of which are Nebraska Children and Families Foundation initiatives. Rosa is a home visitor for Sixpence in Grand Island, where she works with families to help stabilize them in the community and get them connected to local resources, such as the public library, the school system, and area churches.

It was in this role that Rosa met Darla (known as Darlita) and her parents. Darlita is a 3-year-old born to teenage parents from Guatemala and El Salvador, and when Rosa began home visits with the family, it quickly became apparent something wasn’t working. Rosa would bring Nebraska Growing Readers books to her first visit of the month with Darlita and, as Rosa describes it, “we would try to say simple words; she (Darlita) wasn’t able to articulate them. She couldn’t say ‘mom’ or ‘dad’ in either English or Spanish, and she would go into rages.” Rosa could see that Darlita was struggling with language development.

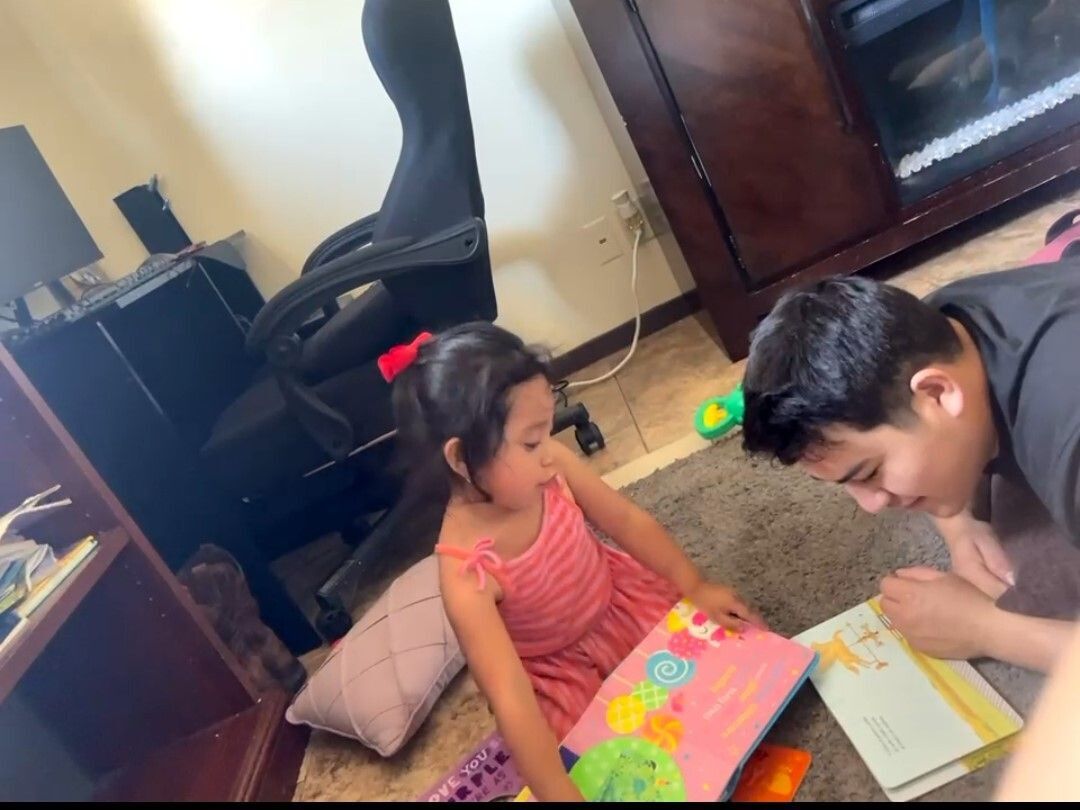

Rosa made reading part of Darlita’s routine. At each home visit, she would dedicate story time where Darlita’s mother or father would sit with her and read. She says of the routine she has established, “what we are trying to do here with our Sixpence is to create a culture of literacy.” This built-in routine of shared-reading has paid off. Not only has Darlita begun to engage with books, but she has also created her own safe space for reading, where she can self-regulate her emotions. In a video Darlita’s mother shared, Darlita, who was having a rough day, takes an NGR book into her safe space (a corner behind the sofa), and turns page after page, pointing to the pictures and naming pictures. In the video, she sits in a pink bucket-style chair sandwiched between the back of the sofa and her small pink kitchen set. She clearly articulates “Mami, “baby,” and other words.

Rosa says that now when she goes for that first visit of the month and takes out the new selection of NGR books, Darlita will “grab them and put them in her safe space.” She adds, “she’s very actively engaged in wanting to go through her books before the session is over.” Rosa points out another benefit of this reading ritual. Because the mother is reading to Darlita in both English and Spanish, her English has improved. She explains, “these books are really great for when we have parents that are English-language learners. The words are small enough and the sentences easy enough to articulate, so they’re able to read to their infants.” And, in doing so, they’re able to improve their own literacy skills.

Rosa says that because some Sixpence families struggle with literacy, she finds it useful to distribute NGR books to all her families. She says that some of her families are quadrilingual and use the books across generations to help improve language skills. She has, for example, a family where the grandmother only speaks K’Iche (Mayan language, second-most spoken in Guatemala) and is using Spanish versions of the books to learn.

Overall, Rosa is very happy to incorporate NGR books into her Sixpence home-visit curriculum. For her, there are multiple benefits to using them. They not only improve literacy skills through families adopting shared-reading habits, but they also do so across generations. In addition, they work well, as in Darlita’s case, as a means of self-regulating. As she puts it, the books “are great for parents who are learning to read; and for the children, they learn fine motor skills, cognitive skills, and self grounding skills.”

Darlita has moved from tearing up books to using them as a self-soothing strategy; she’s gone from an inability to articulate simple words to saying those all important early-bonding words “Mami” and “baby”; she now spends time with her parents bonding over books. This is how cultures of literacy begin, with intergenerational connections and moments of reading together.