When Paw Tha Hser says, “I feel like our language is going away, our Karen community,” she isn’t saying this lightly. Paw Tha is a member of the Karen community that has been persecuted in Myanmar (previously Burma), and she herself spent over 20 years in a refugee camp on the border of Thailand.

Having survived the Burmese Junta’s attempts to wipe out Karen culture, it must have been difficult to watch, when she finally immigrated to Texas, a slower cultural erasure as the next generation of Karen forgot their native tongue.

After a short stay in Texas, she moved to Nebraska and became the Bilingual Liaison for Benson High School in the Omaha Public School system. She worked there for 10 years before joining Parent University last March. It was there that she was contacted by Greta Carlson of Nebraska Growing Readers (NGR), a literacy initiative of Nebraska Children and Families Foundation, who asked her if she would be interested in translating children’s texts into her native Karen.

Paw Tha eagerly accepted. When asked why the project was so important to her, she said, “We should preserve our language for the next generations. That’s why these translations are so important.”

Paw Tha is a part of a larger push by NGR to translate texts into a number of languages. In their first year, the program has been able to translate 54 books in total: 18 into Karen, 2 into Burmese, 5 into Arabic, 5 into Massalit, 11 into Dari, and 13 into Spanish. Paw Tha worked with a team of Karen speaking parents who assisted each other in the translations. She was individually responsible for 3 books, only one of which she was paid for, and she says she wants to do at least 4 more.

She celebrates the communal sense of the work where the group of Karen speakers met and discussed the best translation of parts of the text. She added that it was interesting to debate the clearest Karen translations for English words that have no equivalent in Karen. She says of the NGR books the group works on, “these little books are the beginning” of introducing Karen language and culture to a younger generation of her people. She says, in fact, that the texts benefit not only the children, but also their parents, who can read together with their kids and learn about American culture.

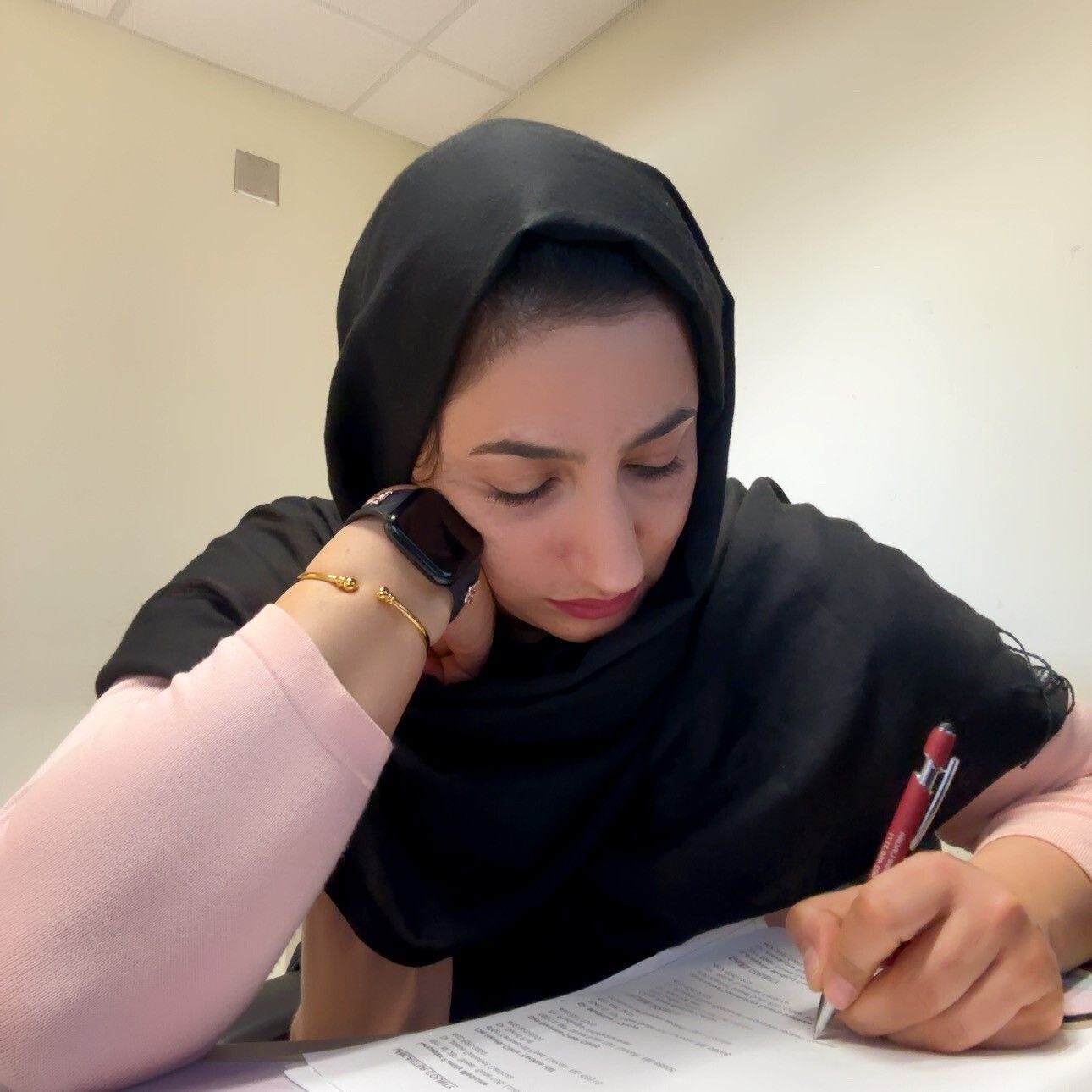

Fariha Mohmand shares a similar sentiment. Fariha, who has been translating texts into her native Dari, is also a refugee who came to the U.S. from Afghanistan. She said that one of the mothers she works with said, “hey, I want to start with this book (an NGR book).” Fariha commented that even though the books are for children, parents who are learning English as a second language can learn from them as well. She adds, “Some of the words are new even for me. Sometimes the books are not just helping the kids, but helping families as well.”

If you follow NGR stories, you might remember Fariha from our story on her son who became a part of the incoming kindergartener program where registered families received up to 100 books for free in the mail. Fariha translated 5 NGR books into Dari, and admits that among them was one of her children’s favorite books about trucks. She says that many of the families she works with respond well to the book and so she thought it would be a good place to start.

Fariha says that her boys have begun to comment on her speaking differently when she switches to Dari, so she doesn’t want them to grow up and be asked, “hey your Afghan, why don’t you speak the language?” The project then is very personal to her.

She tells the story of her son coming home to present the gift card he’d won after reading a number of the books and passing a reading test. She laughs as she recounts the shopping trip where he picked a $400 gift with the $50 card not understanding that the amount was a limit. When she pointed out the limit was $50 he said, “no, I have a gift card, you must get this.”

His pride is her pride. When asked how she felt about undertaking the translations, she said, “I feel so proud. It’s important that I can do this for my community.” Fariha wants to continue translating texts into Dari and to add both her husband’s native Pashtu and Farsi, to the list of translations she wants to accomplish. She says, “as a mom, as a refugee, as a person, I love being a part of this educational project.”

What is clear in speaking with both these women is that the NGR translation project is much larger than children’s books. It’s about cultural heritage; it’s about families connecting; it’s about understanding the culture you’re in and celebrating the culture you come from. The children and families who read these books see a mirror of themselves, but also step through a door into the new place they embrace.